Department of Physics

Welcome to the Department of Physics at Durham

The Physics Department is a thriving centre for research and education.

We are proud that our Department closely aligns the teaching and learning experience for its students with the research-intensive values and practices of the University. Research-led teaching is embedded at all levels from first year laboratory reports to our final year MSci flagship individual research projects.

The Department incorporates the Ogden Centre for Fundamental Physics, is home to the Institute for Particle Physics Phenomenology and the Institute for Computational Cosmology. The Ogden Centre is also the base for our innovative outreach programme for school children and their teachers.

Just got your grades?

We look forward to welcoming you to Physics. Find out what to do next below.

What's new?

Milky Way could be teeming with more satellite galaxies than previously thought

The Milky Way could have many more satellite galaxies than scientists have previously been able to predict or observe.

Working to answer the ultimate question – are we alone in the Universe?

Bright young stars light up UK's National Astronomy Meeting

National Astronomy Meeting 2025 – discover our free public events

National Astronomy Meeting 2025 - exploring Durham’s rich astronomical research

‘World-class’ research showcased during Europe-wide summit

Durham scientists play key role in global space survey as first Rubin Observatory images released

New ‘mini halo’ discovery deepens our understanding of how the early Universe was formed

Astronomers have uncovered a vast cloud of energetic particles surrounding one of the most distant galaxy clusters ever observed, marking a major step forward in understanding the hidden forces that shape the cosmos.

‘World-class’ research showcased during Europe-wide summit

Durham scientists play key role in global space survey as first Rubin Observatory images released

Bright young stars light up UK's National Astronomy Meeting

Young people are at the centre of a major national conference bringing some of the world's finest scientists to the region.

National Astronomy Meeting 2025 – discover our free public events

The Rochester Lecture 2025 will be delivered by Nobel Prize Laureate Prof. Anne L'Huillier

Milky Way could be teeming with more satellite galaxies than previously thought

The Milky Way could have many more satellite galaxies than scientists have previously been able to predict or observe.

Working to answer the ultimate question – are we alone in the Universe?

National Astronomy Meeting 2025 - exploring Durham’s rich astronomical research

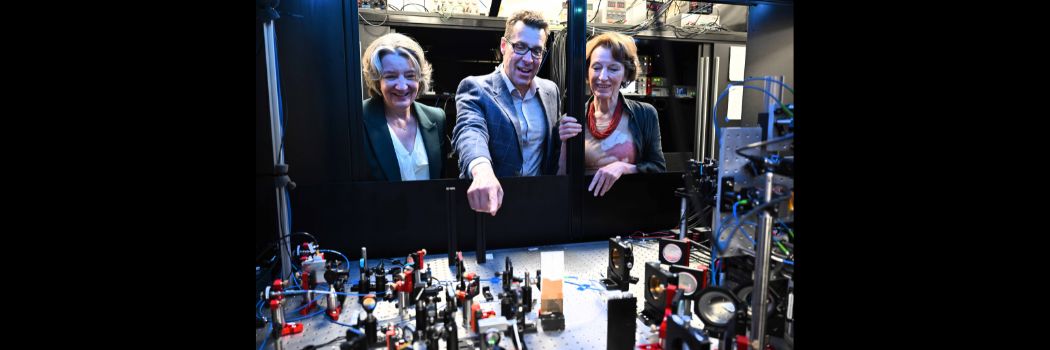

Government Minister visits Ukraine summer camp

The UK’s Higher Education Minister has visited our campus to show her support for an education and recreation summer camp for Ukrainian young people.

Condensed Matter Physics Research Section came together for an Away Day

Celebrating the next generation of North East Physicists

Study with us

Undergraduate study

Find out more about our BSc and MPhys courses.

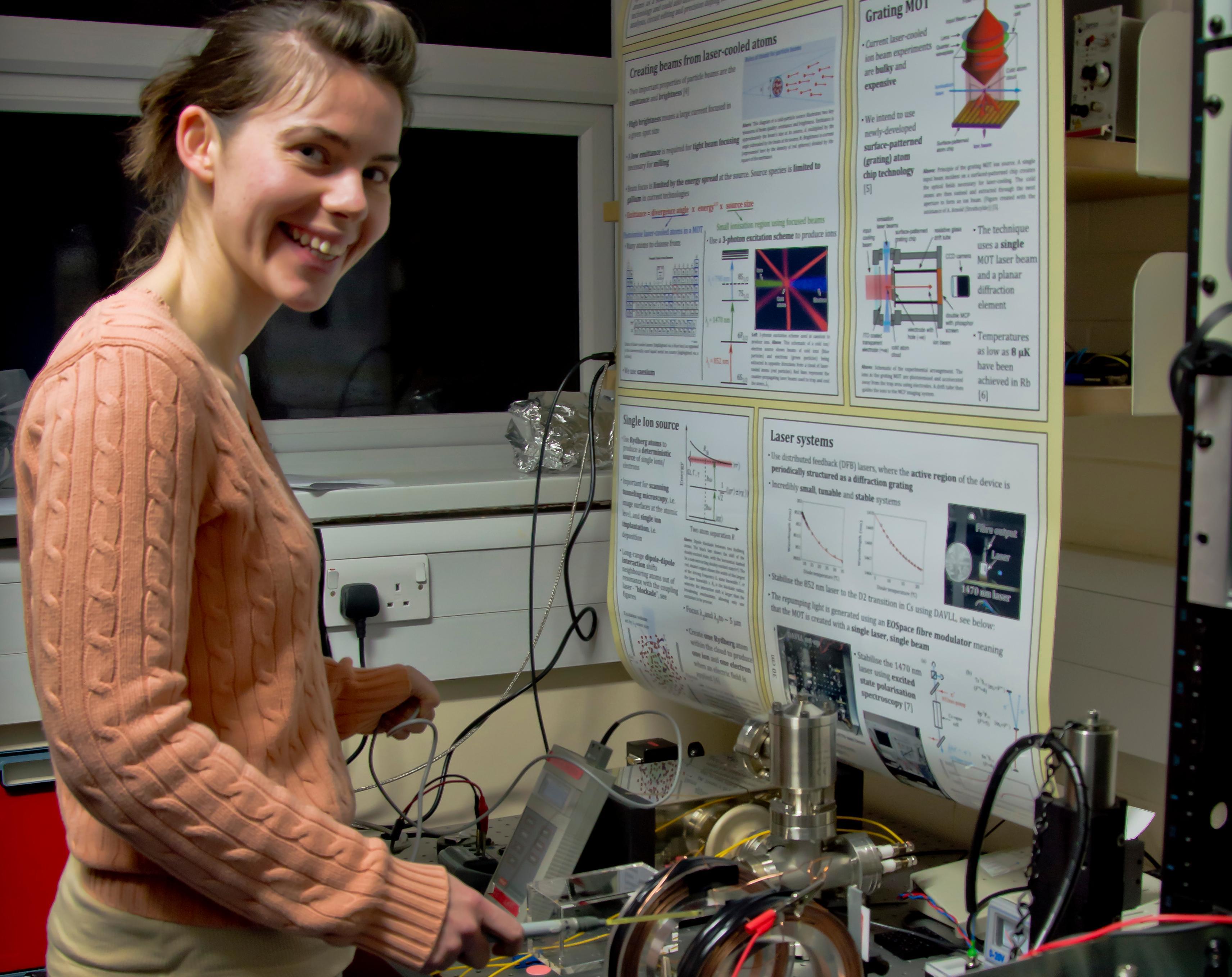

Postgraduate study

Discover more about our taught courses and research degrees.

Our research

We are one of the top Physics Departments in the UK for research, as recognised in repeated assessments and league tables.

Our history

2024 marked 100 years of the Department of Science in Durham University, years that have seen the service of thirteen different Heads of Physics, hundreds of staff and thousands of students. To celebrate this milestone, you can now discover the history of Physics at Durham through the centuries.

From Temple Chevallier to the researchers of today, scroll through our timeline and meet some of the key figures from our history. Watch as some of our most influential academics from past and present talk about their experiences of Durham through the years. Learn about the buildings that have shaped our history, from the creation of the Observatory in the 1800s to the first dedicated building for Physics in the late 1950s, to our major investment in Astronomy going forward.

Look Closer at the Faculty of Science

Whether it’s our world-leading research that seeks to empower and inspire, our commitment to educational excellence across eight academic departments, or our focus on the next generation of scientists through our ground breaking science outreach and engagement. We push forward, break down barriers, asking the big questions and getting answers. Watch our short video to find out why there’s more to science at Durham than meets the eye.

Open Days & Visits

We can offer personal tours of the Physics Department by arrangement, in addition to the University’s standard open day offerings. to discuss a department tour, please see ‘Arrange a personal tour’ below.

Experience Durham by arranging a personal tour

Arrange to have a personal tour of our department buildings and facilities, meet departmental staff and get a feel for what it would be like to study here.

Student updates

What it's been like studying Physics

3rd year Physics student Jack reflects on his studies during the pandemic

Day in the life of a 3rd year Physics student: My Industrial Project

Physics student Gabriel tells us about his Team Project module at Durham

Get in touch

Contact us to find out more about our department.

Department of Physics

Durham University

Lower Mountjoy

South Road

Durham

DH1 3LE

United Kingdom

Questions about studying here?

Check out our list of FAQs or submit an enquiry form.

Your Durham prospectus

Order your personalised prospectus and College guide here.

-(1).png)

/prod01/prodbucket01/media/durham-university/departments-/physics/teaching-labs/IMG_1095.jpg)

/prod01/prodbucket01/media/durham-university/departments-/physics/postgraduates/000583826-ECR-01-3424X2714.JPG)

/prod01/prodbucket01/media/durham-university/departments-/physics/equality-and-diversity/Royal-Society-Flags-Group.jpeg)

/prod01/prodbucket01/media/durham-university/departments-/physics/equality-and-diversity/Royal-Society-Flags-Group.jpeg)

/prod01/prodbucket01/media/durham-university/departments-/physics/staff/VT2A9495-2826X2018.jpeg)

/prod01/prodbucket01/media/durham-university/departments-/physics/telescopes/21AprilC.jpg)

/prod01/prodbucket01/media/durham-university/departments-/physics/buildings/Studio-Libeskind_The-Ogden-Centre_Durham-University_-%C3%82Hufton-Crow_026-3429X2337.jpg)

/prod01/prodbucket01/media/durham-university/departments-/physics/buildings/PhysicsBuilding.jpg)

/prod01/prodbucket01/media/durham-university/departments-/physics/teaching-labs/IMG_3659.jpeg)